I talked in my previous post about Redis eviction policies. In this post, I would like to describe the design behind Dragonfly cache.

If you have not heard about Dragonfly - please check it out. It uses - what I hope - novel and interesting ideas backed up by the research from recent years [1] and [2]. It’s meant to fix many problems that exist with Redis today. I have been working on Dragonfly for the last 7 months and it has been one of the more interesting and challenging projects I’ve ever done!

Anyway, back to cache design. We’ll start with a short overview of what LRU cache is and its shortcomings in general, and then analyze Redis implementation specifically.

LRU

The least recently used (LRU) cache policy evicts items, as the name implies, that were least recently used. It works this way because a cache algorithm strives to optimize the hit ratio, or the probability that its items will be accessed in the future.

If a cache is full, it needs to vacate items to make room for new additions. The cache frees space for new additions by removing the least valuable items, assuming that the least recently used item is also the least valuable.

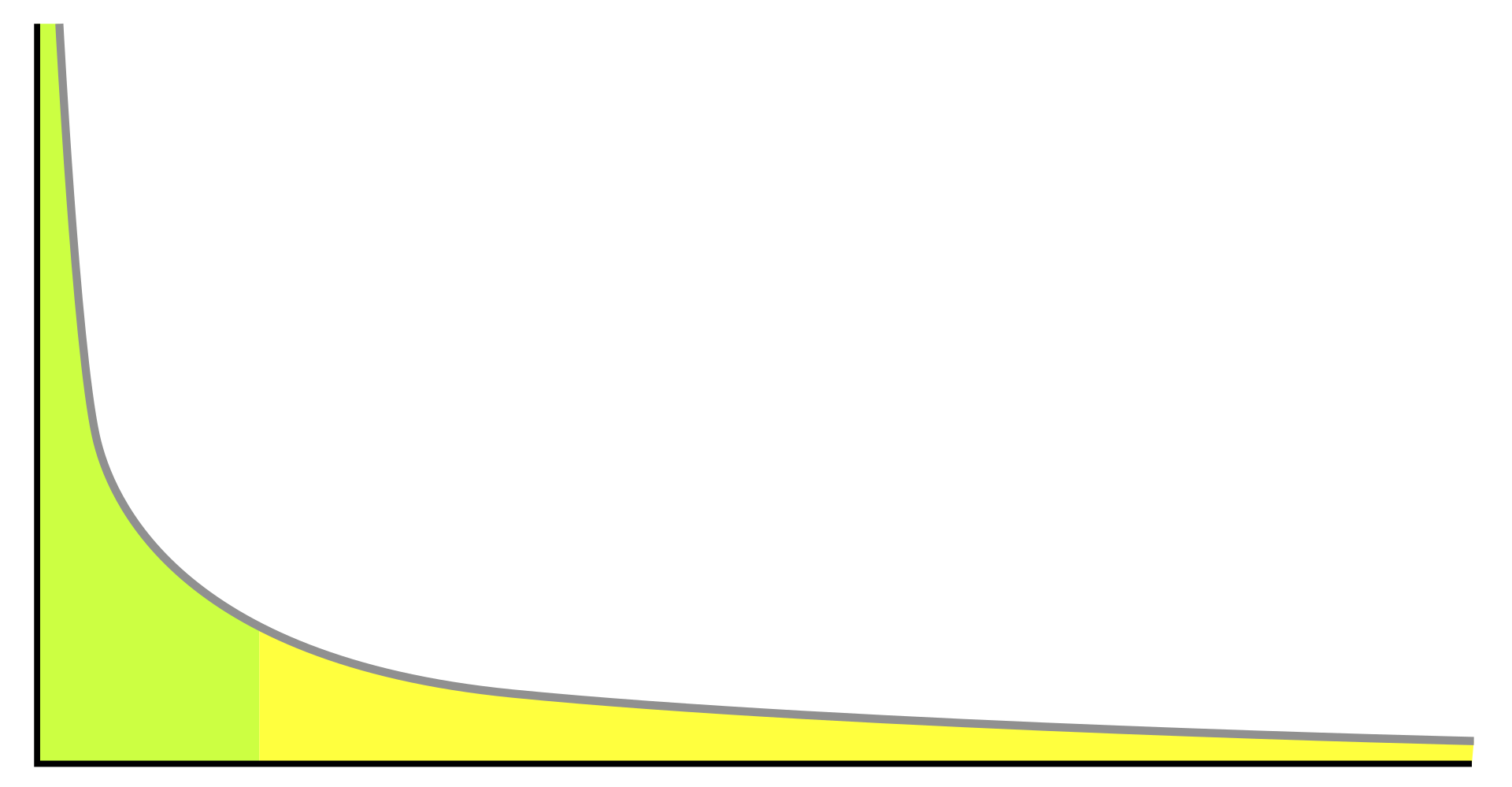

The assumption is reasonable, but unfortunately, this algorithm behaves poorly if the assumption above does not hold. Consider, for example, an access pattern with Long tail distribution. Here, the y-axis represents the normalized access frequency of the items in cache and the x-axis represents the items ordered from highest frequency to lowest.

In this case, lots of newly added “yellow” items with low access frequency could push out rare but valuable “green” items responsible for the vast majority of hits. As a result, the LRU policy may sweep its contents together with valuable “green” entities due to traffic fluctuations.

LRU implementation efficiency

LRU is a simple algorithm that can be implemented efficiently.

Indeed, it maintains all the items in a double-linked list. When an item is accessed, LRU moves it to the head of the list. To vacate LRU items, it pops from the tail of the list. See the diagram above. All operations are done in O(1), and the memory overhead per item is 2 pointers, i.e. 16 bytes on 64bit architecture.

LRU in Redis

Redis implements a few eviction policy heuristics. Some of them are described as “approximated LRU”. Why approximated? Because Redis does not maintain an exact global order among its items like in classic LRU. Instead, it stores the last access timestamp in each entry.

When it needs to evict an item, Redis performs random sampling of the entire keyspace and selects K candidates. Then it choosed the item with the least recently used timestamp among those K candidates and vacates it. This way, Redis saves 16 bytes per entry needed for ordering items in one global order. This heuristic is a very rough approximation of an LRU.Redis maintainers have recently discussed the possibility of adding an additional heuristic to Redis by implementing a classic LRU policy with global order but eventually decided against it.

Dragonfly Cache

Dragonfly implements cache that:

- is resistant to fluctuations of recent traffic, unlike LRU.

- Does not require random sampling or other approximations like in Redis.

- Has zero memory overhead per item.

- Has very small

O(1)run-time overhead.

It’s a novel approach for cache design has not been suggested before in academic research.

Dragonfly Cache (dash cache) is based on another famous cache policy from 1994 paper - “2Q: A Low Overhead High Performance Buffer Management Replacement Algorithm”.

2Q addresses the issues with LRU by introducing two independent buffers. Instead of considering just recency as a factor, 2Q also considers access frequency for each item. It first admits recent items into a so-called probationary buffer (see below). This buffer holds only a little part of the cache space, say less than 10%. All newly added items compete with each other inside this buffer.

Only if a probationary item was accessed at least once, will it be proven as worthy, and upgraded to the protected buffer. By doing so, it evicts the least recently used item from the protected buffer back to probationary buffer. You can read this post for more details.

2Q improves LRU by acknowledging that just because a new item was added to the cache - does not mean it’s useful. 2Q requires an to have been accessed at least once before to be considered as a high quality item. In this way, 2Q cache has been proven to be more robust and to achieve a higher hit rate than LRU policy.

Dashtable in 60 seconds

For a deep dive on Dashtable’s use in Dragonfly, I recommend you reading this post or the original paper.

For our purposes today, we need to know the following facts about Dashtable in Dragonfly implementation:

- It’s comprised of segments of constant size. Each segment holds 56 regular buckets with multiple slots. Each slot has space for a single item.

- Dashtable’s routing algorithm uses item’s hash value to compute its segment id. In addition, it predefines 2 out of 56 buckets where the item can reside within the segment. The item can reside in any free slot in those two buckets.

- In addition to regular buckets, a Dashtable segment manages 4 stash buckets that may gather overflow items that do not have space in their assigned buckets. The routing algorithm never assigns stash buckets directly. Instead, only if its 2 home buckets are full, the item is allowed to reside in any of 4 stash buckets. This greatly increases segment’s utilization.

- Once a segment becomes full, and there is no free place for a new item in its home buckets nor in stash buckets, the Dashtable grows by adding a new segment and splitting the contents of the full segment roughly in half.

The point at which a segment becomes full is a convenient time to add any type of eviction policy to Dashtable, because this is when Dashtable grows. Moreover, in order to prevent growth of Dashtable, we can only evict items from a full segment. This constitutes a very precise eviction framework that operates in O(1) run-time complexity.

2Q implementation

Dragonfly expands on the ideas above. A naive solution would be to divide hashtable entries into two buffers: a probationary buffer with FIFO ordering, and the protected buffer employing LRU linked-list. That would work but it would require using additional metadata and waste precious memory.

Instead, Dragonfly leverages the unique design of Dashtable and uses its weak ordering characteristics for its advantage.

To explain how 2Q works with Dashtable, we need to explain how we define probationary and protected buffers there, how we promote a probationary item into protected buffer and how we evict items from the cache.

We overlaid the following semantics on the original Dashtable:

- Slots within a bucket now have rank or precedence. A slot on the left has the highest rank

(0), and the last slot on the right has the lowest rank(9). - Stash buckets within a segment serve as a probationary buffer. When a new item is added to the full segment, it’s been added into a stash bucket at slot 0. All other items in the bucket are shifted right, and the last item in the bucket is evicted. This way the bucket serves as a FIFO queue for probationary items.

- Every cache hit “promotes” its item:

- if the item was in a stash bucket, it’s moved immediately into its home bucket to the last slot.

- if it was in a home bucket at slot

i, it’s swapped out with an item at sloti-1. - an item at slot

0stays in the same place.

- When a probationary item is promoted to the protected bucket, it’s moved to the last slot there. The item that was there before is demoted back into the probationary bucket.

Basically, Dash-Cache eviction policy is comprised of an “eviction” step described by (2) and the positive reinforcement step described by (3).

That’s it. No additional metadata is needed. High quality items will come to reside at high rank slots in their home buckets very quickly, while newly added items compete with each other within stash/probationary buckets. In our implementation each bucket has 14 slots, meaning that each probationary item can be shifted 14 times before being evicted from the cache, unless it proves its usefulness and is promoted. Each segment has 56 regular buckets and 4 stash buckets; therefore we have 6.7% of total space allocated for a probationary buffer. It’s enough to catch high quality items before they are evicted.

I hope you enjoyed reading how Dragonfly cache design utilizes seemingly unrelated concepts together to its advantage.

I want to thank Ben Manes, the author of wonderful caffeine package for early comments and the guidance on how to use caffeine simulator in order to compare Dragonfly Cache to other caches.